In case T 314/20, EPO Board 3.3.04 provides a review of the interpretation of headnote 2 of G 2/21 by Board 3.3.02 in the underlying decision T 116/18 and challenges certain assumptions made by said board (reason 6.13 of T 314/20). Board 3.3.04 was also confronted with the patentee’s request for a referral to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) based on an alleged need for further clarification of headnote 2 of G 2/21 and allegedly divergent interpretations adopted by Board 3.3.04 in T 314/20 and yet another board (3.3.07) in T 1525/19 (point X and reason 13 of T 314/20).

While the decision in T 314/20 was announced at the oral proceedings of November 16 2023, the written decision was published more than a year later on December 20 2024, which indicates that the board took the time to conduct a very detailed and reflective analysis in this complex environment.

It is not surprising that the abstractness of headnote 2 of G 2/21 provides extended room for interpretation. As stated by the board in T 314/20, the relationship of the requirements of G 2/21 to the different types of previous case law (reference is also made to the authors’ article in epi Information, issue 1, 2024) “remains to be defined, particularly in terms of whether, and to what extent, they replace, align with, or modify it” (reason 6.12.5 of T 314/20). The referral in T 314/20 was denied also based on a concern that “it is at least uncertain whether the Enlarged Board of Appeal would introduce further definitions if asked for additional guidance” (reasons 12 to 20 of T 314/20).

Summary of the facts of T 314/20

The relevant claim refers to a combination product comprising two concrete compounds: “A pharmaceutical composition comprising the glucopyranosyl-substituted benzene derivative [empagliflozin] in combination with the DPP IV inhibitor [linagliptin] or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof.”

The difference from the closest prior art is the specific selection of empagliflozin and linagliptin (reasons 3 and 4 of T 314/20). The G 2/21 discussion centred on the purported technical effect of an increase in glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels (resulting in an improved diabetes treatment) obtained with this combination and as allegedly shown in post-filed data (point X and reasons 5 and 6.5 of T 314/20).

An unexpected technical effect such as an improvement over the prior art is regularly required, since the selection of a specific combination from a more generic disclosure with merely an expected function is often considered arbitrary, therefore lacking inventive step (also see reason 10.4.3 of T 314/20). Thus, the dispute in T 314/20 focused on whether the patentee can rely on the alleged improvement for arguing inventive step. As only data provided after the filing date of the corresponding patent application possibly supported said effect (reason 6.11 of T 314/20), the situation in T 314/20 can be considered a typical “G2/21 situation”.

The board found that the patentee cannot rely on the purported technical effect in light of decision G 2/21 (reason 6.11 of T 314/20). Inventive step was then denied overall (reason 11 of T 314/20). In coming to its conclusion, the board not only evaluated G 2/21 itself but also closely reviewed the detailed – however, still general – legal test criteria another board (3.3.02) in its decision T 116/18 (G 2/21 underlying case) inferred from the much more abstract guidance provided by G 2/21.

Evaluation of the interpretation of G 2/21 in the underlying case T 116/18

In Board 3.3.02’s referral to the EBA in T 116/18, it discussed at least two lines of case law setting the standard for accepting post-filed data to support an alleged technical effect: the effect must be ‘ab initio plausible’ or not be ‘ab initio implausible’; the latter standard being significantly lower and usually shifting the burden of proof to the opponent.

The EBA did not, however, directly answer the questions and did not refer to these two standards in the relevant headnote 2 of G 2/21, which reads: “A patent applicant or proprietor may rely upon a technical effect for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would derive said effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.”

In T 314/20, Board 3.3.04 provided an analysis of the reasoning in the final decision T 116/18, in which Board 3.3.02 accepted the technical effect in question based on post-filed data using as a test criterion, in essence, an ‘ab initio implausibility’ standard and did not require a literal disclosure “by way of a positive verbal statement” of the respective effect in the application as filed. Inventive step was ultimately acknowledged. Board 3.3.04 states that it “faces two issues with the interpretation of decision G 2/21” in the underlying case (reasons 6.13.4 and 6.13.5 of T 314/20).

First, although “the relevant Board [Board 3.3.02 in T 116/18] stated […] that in decision G 2/21 the Enlarged Board did not refer to any ‘plausibility’ standards […] but instead adopted new requirements” and “that when deciding whether a patent applicant or proprietor may rely on a purported technical effect for inventive step, it was the requirement(s) defined by the Enlarged Board in point 2 of the order that had to be applied, rather than simply using any rationale developed in the previous plausibility case law” (reason 6.13.6 of T 314/20), “the Board [again, Board 3.3.02 in T 116/18] effectively adopted what it defined in the referral T 116/18 as the ‘ab initio implausibility’ standard” (reason 6.13.8 of T 314/20; see a similar conclusion by the authors in an article in epi Information, issue 1, 2024). According to the board, this is not stated in G 2/21 (reason 6.13.9 of T 314/20).

Second, while the board in T 116/18 “concluded that a positive verbal statement of the technical effect […] in the patent application as originally filed was not necessary” for the requirements of G 2/21 to be met, “such a statement is also not to be found in decision G 2/21” (reason 6.13.9 of T 314/20). The board considered that “the passages of decision G 2/21 referred to by decision T 116/18 do not lead to the conclusion that the standard of disclosure that applies to Article 87 EPC [European Patent Convention] […], Article 123(2) EPC or Article 54(1) EPC […] is excluded” when assessing whether the requirements of G 2/21 are fulfilled. “While this may be a valid approach, it does not follow from the text of decision G 2/21” (reason 6.13.11 of T 314/20).

The board in T 314/20, however, also stated that it “does not need to give a definitive answer as to whether it can endorse all the conclusions of decision T 116/18”. It did agree with the view in T 116/18 that the purpose of the G 2/21 criteria is “to prevent patents from being granted for inventions that are not complete at the filing date”; i.e., “speculative applications” (reasons 6.13.3 and 6.14 of T 314/20).

The board found that “the increase in active GLP-1 levels […] forms the basis of an invention which has not been made or disclosed at the filing date of the application. Consequently, this technical effect cannot be taken into account for formulating the objective technical problem” (reason 6.28, in consideration of reasons 6.14 to 6.27, of T 314/20).

Of course, it remains open for the reader as to whether this board would have come to a different conclusion when applying the ‘ab initio implausibility’ standard outlined by Board 3.3.02 in T 116/18. Although the boards express an agreement on preventing patents from being granted for inventions that are not complete at the filing date – i.e., speculative applications – they use different tests in terms of how to evaluate this.

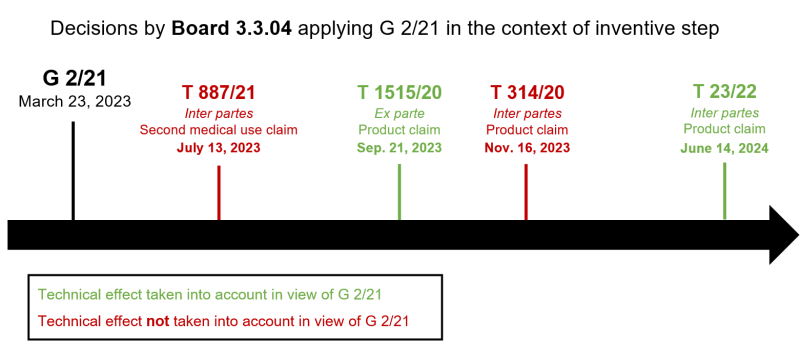

The case law applying G 2/21 in the context of inventive step is currently dominated by boards 3.3.02 and 3.3.07. Nevertheless, further decisions by Board 3.3.04 are also available (see the overview below). In contrast to T 314/20, those do not refer to the underlying case T 116/18. But, in T 887/21, Board 3.3.04, similarly as in T 314/20, had already stressed that “[a]n invention cannot be based solely on knowledge made available only after the effective date” (reason 2.15.3 of T 887/21).

Request for referral to further clarify the G 2/21 criteria denied

During the oral proceedings in T 314/20, the patentee requested a new referral to the EBA to further clarify the test of G 2/21. The underlying fact pattern – including relevant claim limitations, prior art, and post-filed data of the current case – was allegedly the same as that of case T 1525/19. The fact that the deciding Board 3.3.07 in said other case concluded differently from Board 3.3.02 in the current case, even though both boards applied G 2/21, allegedly supported the argument of different interpretations by the boards warranting a referral (points VII and X, and reason 13 of T 314/20).

In T 1525/19, the relevant claim reads: “A solid pharmaceutical dosage form comprising linagliptin as a first active pharmaceutical ingredient in an amount of 5 mg and [empagliflozin] as a second pharmaceutical ingredient in an amount of 10 mg or 25 mg and one or more excipients […]”.

The board rejected the request, as:

The facts of the cases were not the same;

It was not known whether the boards indeed applied different interpretations of G 2/21; and

Even if there were a divergence, a referral would only be mandatory if a board intends to depart from an interpretation of the EPC given by the EBA (and not merely by another board).

Furthermore, “the Enlarged Board of Appeal deliberately chose not to define the requirements set out in decision G 2/21. Nor did it argue that the case law underlying questions 2 and 3 of the referral in T 116/18 had been rejected. Against this background, it is at least uncertain whether the Enlarged Board of Appeal would introduce further definitions if asked for additional guidance.” In addition, “no […] divergent lines of case law are apparent”. And finally, “any tenable interpretation of the requirements introduced in decision G 2/21” would lead to the same conclusion in the present case (reasons 12 to 20 of T 314/20); however, without providing any detailed reasoning at this point.

Also in T 1525/19, a request for referral on the interpretation of decision G 2/21 in view of allegedly diverging views of Board 3.3.07 in T 1525/19 and Board 3.3.04 in T 314/20 was denied (reasons 8.5 and 8.6 of T 1525/19).

Can the EBA’s requirements be further defined?

In G 2/21, the EBA detected a “common ground” among the previous ‘plausibility’ case law (reason 71 of G 2/21) and ultimately formulated the ‘encompassed’ and ‘embodied’ criteria (reason 94 of G 2/21). However, the EBA also emphasised that “it is the pertinent circumstances of each case which provide the basis on which a board of appeal or other deciding body is required to judge, and the actual outcome may well to some extent be influenced by the technical field of the claimed invention” (reason 95 of G 2/21). Although the EBA was “aware of the abstractness” of the established guiding principles, those should, “[i]rrespective of the actual circumstances of a particular case, […] allow the competent board of appeal or other deciding body to take a decision […]” (reason 95 of G 2/21).

Board 3.3.02 in T 116/18 provided an interpretation of headnote 2 of G 2/21 and applied a test using essentially an ‘ab initio implausibility’ standard for assessing whether the patentee can rely on the purported technical effect. However, as shown by the critical review in T 314/20, this test of T 116/18 is not applied by all boards. Decisions may thus not only depend on the facts of the case and/or the technical field (T 116/18 concerned insecticides, whereas T 314/20 concerned medicaments) but may also be influenced by different views of different boards regarding the requirements of headnote 2 of G 2/21.

It remains to be seen whether there will be, after all, another referral by one board requesting further clarification of the requirements in the (near) future, but the reluctance of the boards to refer this again is evident. Also, the question arises whether further definition of the requirements of G 2/21 is in fact possible, or whether the ‘encompassed’ and ‘embodied’ criteria of G 2/21 are already the ‘common minimum’, although, from a user perspective, less variability and more certainty would be highly welcome.