“In recent legal debates, the patentability of AI-generated inventions has been contentious. Historically, only humans were considered inventors, anchored in notions of personhood and intellect. Yet, in a bold move, South Africa and Australia's Federal Court recognised AI, specifically DABUS, as a potential inventor in 2021, defying conventional views. Proponents argue that this accommodates modern innovation trends, while sceptics raise concerns about ownership rights, potential inundation of trivial patents, and diminished human oversight. With patent laws varying globally, the landscape remains dynamic. As AI's role in R&D grows, more countries could re-evaluate their stances, reshaping the intellectual property (IP) sphere.”

Are you surprised by the depth and flow of that introduction? Here's the twist: that paragraph was created by an AI. Today's AI is at the forefront, seamlessly blending into roles traditionally held by humans, and yes, that is highly likely to include inventions.

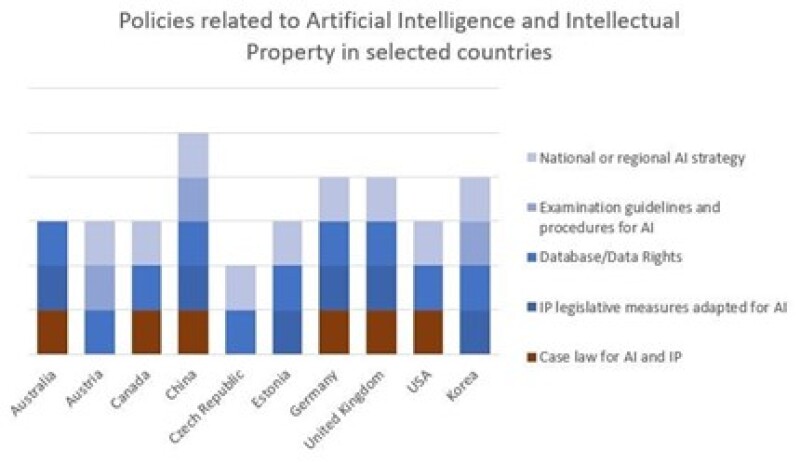

The concept of accepting AI as an inventor is relatively novel, with different countries adopting varying stances. Taking the matter from the beginning, the graph below shows different AI policies that leading economies adopt. These policies primarily encompass database rights and national AI strategies. A noteworthy example of best practices is the series of consultations held in the UK aimed at regulating AI-generated inventions.

Source: based on WIPO

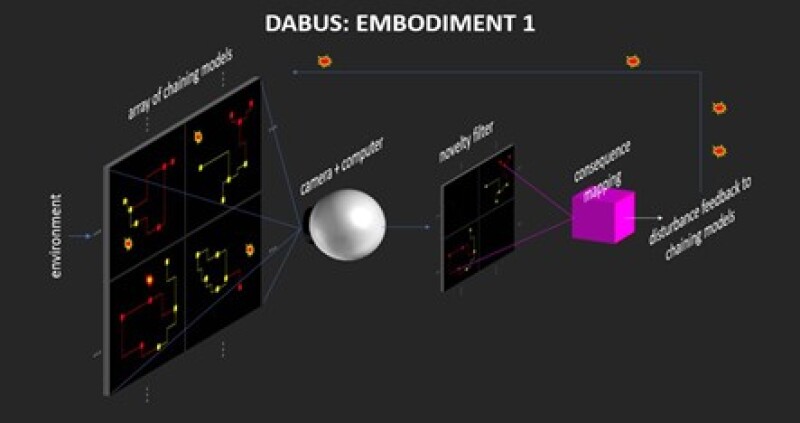

The discussion on whether an AI system can be an inventor began to be argued over after the development of DABUS, an AI system created by Dr. Stephen Thaler.

DABUS has claimed to have invented two novel products:

A food container that uses fractal geometry, which enables rapid reheating; and

A flashing beacon for attracting attention in an emergency.

Dr. Thaler and Prof. Ryan Abbott and his team of attorneys have started to file applications to patent offices worldwide and aimed to establish precedents, questioning whether AI can be an inventor. The project is called “The Artificial Inventor Project”. It is intended to promote dialogue about the social, economic, and legal impact of frontier technologies such as AI and to generate stakeholder guidance on the protectability of AI-generated output, as they stated on their official website.

To assess these developments, one must delve into the outcomes of the DABUS team's applications to various patent offices worldwide within the scope of this project.

United States

In July 2019, Dr. Thaler submitted patent applications for two DABUS inventions to the USPTO (below), listing DABUS as the sole inventor. However, the USPTO deemed them incomplete without a valid human inventor. After Dr. Thaler requested a review of the decisions, the District Court concluded that an ‘inventor’ under the Patent Act must be an ‘individual’, and the plain meaning of individual is a natural person. The court emphasised that inventorship is a concept that requires a mental act; therefore, an AI cannot be the inventor.

Dr. Thaler appealed in June 2022. This case became the first in which the Federal Circuit explicitly addressed whether an AI machine could be an inventor under the Patent Act. Consequently, the Supreme Court has held that ‘individual’ refers to human beings, and ‘inventors’ must be human beings (Thaler v Vidal, US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, August 5 2022). So, it was affirmed that only human beings could be named as inventors on US patents, and AI was excluded from being listed as an inventor.

In June 2023, the US Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on AI and intellectual property (IP) in relation to patents, innovation, and competition. There, Prof. Abbott asked Congress to consider modifying the Patent Act to protect AI-generated inventions (below) by prohibiting patentability from being determined based on how an invention is made.

The UK, the EPO, and New Zealand

Thaler’s applications to the UKIPO, the EPO, and New Zealand encountered similar outcomes to those filed before the USPTO.

The UKIPO rejected Thaler’s DABUS applications on the grounds that DABUS is not a person, so it cannot be considered an inventor (BL O/741/19, UKIPO, December 4 2019). The High Court and the Court of Appeal upheld this decision, deeming Thaler’s withdrawal (Thaler v Comptroller, EWCA Civ 1374 September 21 2021). Thaler subsequently appealed to the UK Supreme Court, where the matter is still pending. If the UK Supreme Court rules in Thaler's favour, it will mark the world's first supreme-level court to deliberate on this issue.

Similarly, Thaler filed two European patent applications with the EPO in 2018, both of which were rejected. The EPO determined that the inventor designated in a European patent must be a natural person. The Legal Board of Appeal, in its preliminary opinion, stated that, under the European Patent Convention, the inventor designated in a patent application must be a person with legal capacity. In December 2021, the Legal Board of Appeal dismissed Thaler’s appeal. Thaler’s latest divisional application, in which he is named as the inventor, remains pending before the EPO.

A similar reason to that given in the UK and EPO was provided in New Zealand. In January 2022, the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (IPONZ) deemed a patent application filed by Dr. Thaler as void, citing the absence of an identified inventor on the patent applications. IPONZ concluded that DABUS could not be considered "an actual devisor of the invention", as required by the Patents Act 2013. In March 2023, the High Court upheld IPONZ's decision.

Australia

The Australian Federal Court has rendered a promising decision on the inventorship of AI, which proved to be relatively short-lived. In September 2019, Dr. Thaler filed an application naming DABUS as the inventor. The Australian Patent Office (APO) rejected the application, and Thaler appealed to the Federal Court.

In July 2021, the Federal Court ordered the APO to reconsider the application. This became the first court judgment allowing an AI machine to be named as an inventor, stating that “an inventor as recognised under the Act can be an artificial intelligence system or device. But such a non-human inventor can neither be an applicant for a patent nor a grantee of a patent” (Thaler v Commissioner of Patents, FCA 879, July 30 2021).

However, the APO appealed the decision, in which they succeeded In April 2022 before the Full Court of the Federal Court. The court stated, "The origin of entitlement to the grant of a patent lies in human endeavour." In November 2022, Thaler’s special leave to appeal was refused by the High Court.

Germany

The German Federal Patent Court, on the other hand, delivered a distinct judgment.

Upon rejection of Dr. Thaler's application by the German Patent Office, also rejected and appealed before the Federal Patent Court in November 2021, the court acknowledged that AI inventions are patentable. However, the court stipulated that the inventor must be presented as a natural person in the application.

This decision made it possible to include AI's involvement in a patent application, sidestepping the debate over who could be deemed the inventor. The court set out that the one responsible for the invention must be identified as the inventor on the form, and details regarding the contribution of an AI system may be added as supplementary information. The decision is under appeal to the Supreme Court.

South Africa

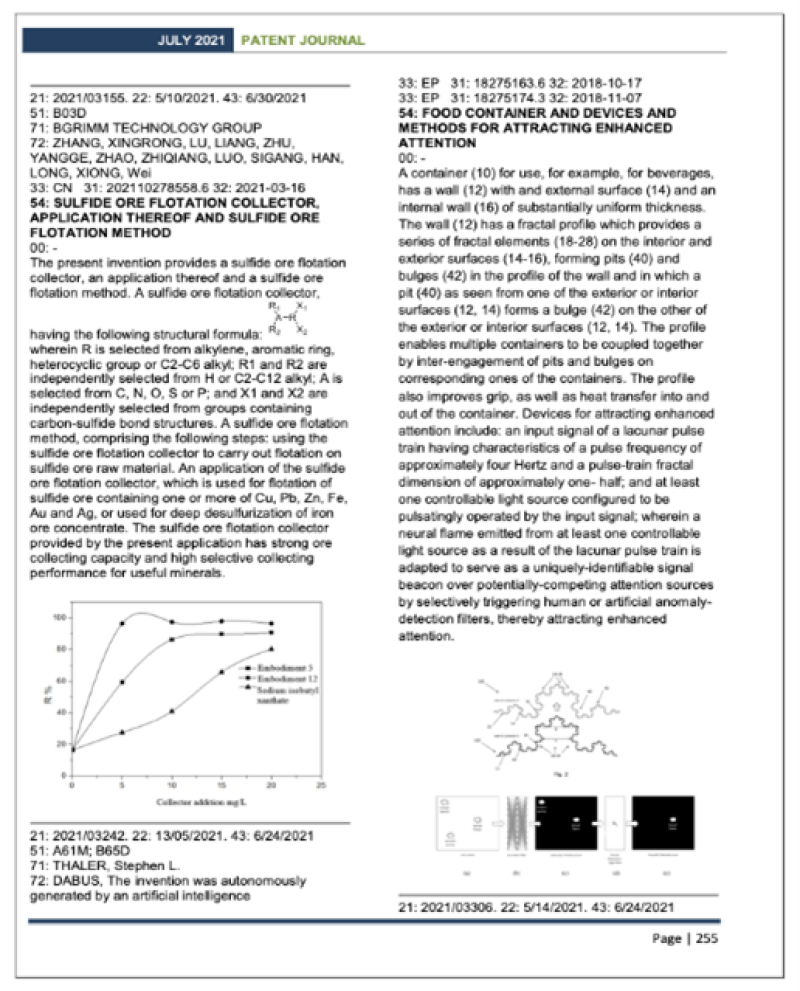

Unique proceedings took place in South Africa, where the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) accepted Dr. Thaler's application for a patent related to inventions generated by DABUS. In July 2021, the CIPC issued a patent issuance notice (below), thereby granting the world's first patent for an AI invention without a human inventor being named.

In this case, the AI's owner holds the patent, and the AI is designated as the inventor. However, it should be noted that South Africa has a depository system regarding patent applications, and it does not conduct any substantive examination on applications.

General overview and assessment of Turkey’s position

In Turkish patent law, the "actual ownership of the right" principle dictates that the individual who creates or develops IP is recognised as the rightful owner. Article 109/1 of the Industrial Property Law (IPL) states that "the right to obtain a patent belongs to the inventor or his legal successors, and it is possible to assign this right to others". Evidently, Turkish patent law does not permit AI to be designated as an inventor in patent applications.

For an invention to be patented, it must:

Be novel;

Involve an inventive step; and

Be applicable to industry.

These will also be considered in the patentability assessment of an invention developed by AI. The legal nature of the inventor is not listed among the patentability criteria, as the lawmaker did not even consider the possibility of AI being an inventor when drafting the provisions.

Turkish law maintains its current stance, but it is vital to bear in mind that there have been no legal precedents addressing this matter, as seen in Dr. Thaler's cases, and there have been no applications to the Turkish Patent and Trademark Office designating AI as the inventor in Turkey. Consequently, this matter remains open to debate and contemplation regarding potential scenarios.

Nevertheless, Gün + Partners would expect Turkey’s approach to be similar to that of the EPO. Indeed, Turkey is a signatory of the European Patent Convention, and it was also designated in the DABUS filings, which means that if the patent application by Dr. Thaler was registered before the EPO, it would also be registered in Turkey.

For Turkish law, and many other countries, the current challenge revolves around the potential outcomes if AI were allowed to be recognised as an inventor. Therefore, the initial step is to ascertain the legal status of AI and seek a resolution to this issue, potentially through amending the IPL or establishing legal precedents.

There is no regulation in Turkey for AI yet. The Turkish Civil Code (the Code) regulates natural and legal persons. According to the Code, every individual has the capacity to exercise rights, and all human beings are equal in terms of their rights and obligations within the legal system. The Code also regulates the capacity to act, and, accordingly, a person who has the capacity to act can acquire rights and incur debts through their actions. The conditions of this capacity are also regulated under the Code. Legal entities, on the other hand, are subject to all rights and obligations other than those that are inherently related to human beings, such as sex, age, and kinship, and legal entities acquire the capacity to act by having the necessary organs.

As some Turkish scholars argue, AI should be considered a legal person. However, this may not be a real person as in the case of human beings, but a legal entity such as an association, since it is similar to the relationship between an association and its board members (

But, according to another perspective, Roman law may be an option for solving AI's legal personality problem. This idea suggests that the status of enslaved people in Roman law can be considered and applied as an example of the status of AI in terms of holding economic and IP rights. In Roman law, under the peculium system, enslaved people were able to have limited, yet legal, relations with third parties even if they were considered the ‘property’ of someone.

Similarly, AI can hold IP rights, and only for that limited value can it be held responsible for the legal consequences of its actions. It can be named as an inventor for an invention if the other requirements for patentability were fulfilled in the invention without meaning that AI is an actual person and holds the right of a real person. In this way, the issue of who will own the rights of AI and the responsibility matter could be solved, at least for now.