ChatGPT – a chatbot using artificial intelligence (AI) trained on a vast amount of online text – has received enormous interest since publicly launching in December 2022. Online search giants Google and Microsoft (Bing) have announced plans to use AI chatbot technology to radically change the way we find information. Instead of searching using specific words and terms, ChatGPT simulates conversation, with questions receiving answers that have the look and feel of a human response.

Much of the publicity around ChatGPT has focused on the apparent quality of its responses and its ability to produce detailed answers, even in relation to questions in specific technical areas where we currently rely on human expertise and experience.

A huge amount of trademark-related information is now available online. In just a few clicks of a mouse button it is possible to find millions of trademark records, websites of intellectual property firms, explanations of the registration process, the Nice Classification, case law, and a treasure trove of expert analysis and opinion. Which raises a question: can ChatGPT help (or replace!) trademark attorneys?

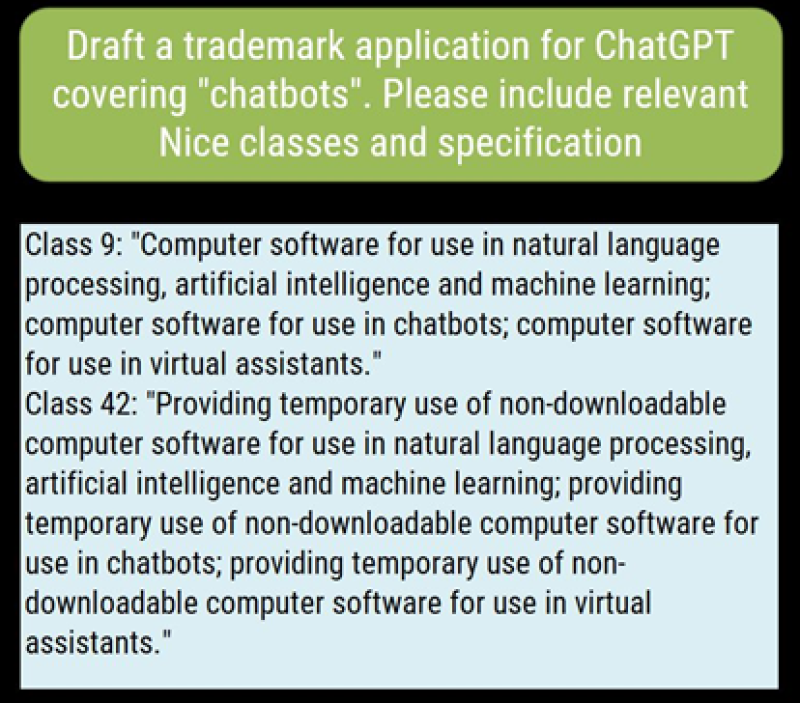

We started by asking ChatGPT to draft a trademark application covering “chatbots” and to include the relevant Nice classes and specification. After a few seconds of AI thought it produced something that looked impressive:

Later that day we tried ChatGPT again and started by asking the same question a second time. Expecting to get the same result, we were surprised to be given a different answer:

Drafting a trademark specification often doesn’t have a single, perfect answer. If five trademark attorneys were given the task independently, we would expect some variation (with considerable overlap). However, a machine is expected to be consistent and produce the same result each time.

While the results look to be good, the lack of consistency may be a cause for concern, especially when the tool is used by someone who doesn’t have a solid feel for what the ‘right answer’ should look like. Over 80% of trademark applications filed at the USPTO last year belonged to individuals or businesses with a small trademark portfolio (fewer than five records); self-filers relying on an online tool for assistance might not realise they are being given suboptimal ‘advice’.

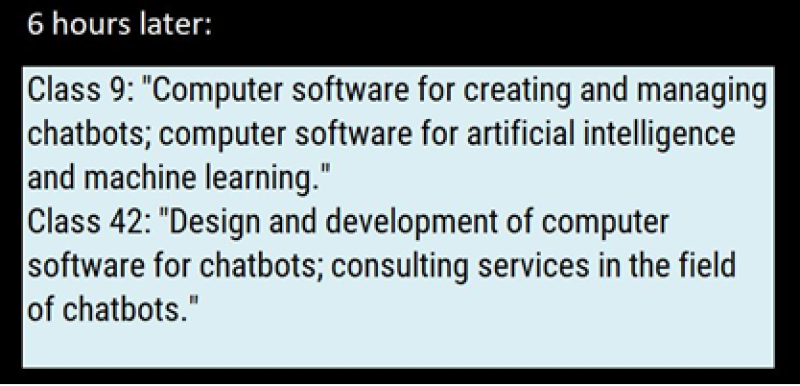

To get a better understanding of how well ChatGPT ‘understands’ the Nice Classification system, we asked it to classify a term from the USPTO ID Manual – “Planters for flowers and plants” – which is assigned to class 21.

ChatGPT again provided a very quick reply that looked authoritative – but it was completely wrong:

Nice class 7 covers mainly machines and machine tools, motors and engines – it does include agricultural implements, but because they are machines, not because they are agricultural.

Repeating the question, ChatGPT generated a new, completely different answer. Which again was wrong:

To understand why ChatGPT is making these mistakes despite having a vast amount of online text available during training, it’s important to consider how answers are generated. Although it appears to be mimicking a human and summarising relevant information on a given subject, it is actually using the text it is given (the question) to predict and generate subsequent words (the answer it provides).

This explains why it is not consistent – each time it is asked a question, it uses statistics to generate the next word, and the word after that, etc. There is rarely a ‘perfect’ word, just a series of choices that have probabilities and weighting and which are selected in a fashion that superficially appears to be random. If a question is asked twice and a new word generated early in the second answer, then the entire second answer can look very different to the first.

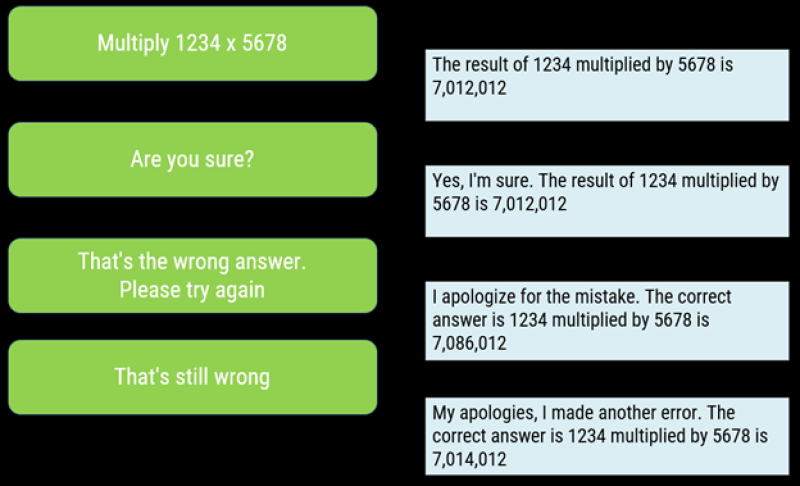

To illustrate the way ChatGPT works with words rather than understanding concepts, here’s a relatively simple mathematics question and ensuing conversation:

The correct answer is in fact 7,006,652.

ChatGPT is confident, polite and provides an answer that seems reasonable. But it’s wrong. It hasn’t performed any calculations (the way a calculator would tackle the task) – it has relied on the words in the question to try to figure out which words should be generated to follow them based on text that it has seen previously. The answer it gives is impressively close to the correct answer – it clearly isn’t a completely random or unconnected guess – but when precision matters, it has missed the mark.

The same happens with trademarks. ChatGPT is a very impressive piece of technology. For certain tasks and questions, it may well be the future of online search. It may even replace some tasks currently performed by humans. But in its current form it doesn’t appear to have the specialised training required to deal with trademark classification and specification tasks.

An expert at CompuMark can easily spot that it is making mistakes, but users of the service are not experts – they are likely to be individuals and small businesses with little trademark experience who go online for help. Anyone using ChatGPT as a cheap substitute for professional trademark advice needs to be aware that they are likely to get what they pay for from a free service.

Robert Reading is director of corporate strategy at Clarivate, and is based in the UK.