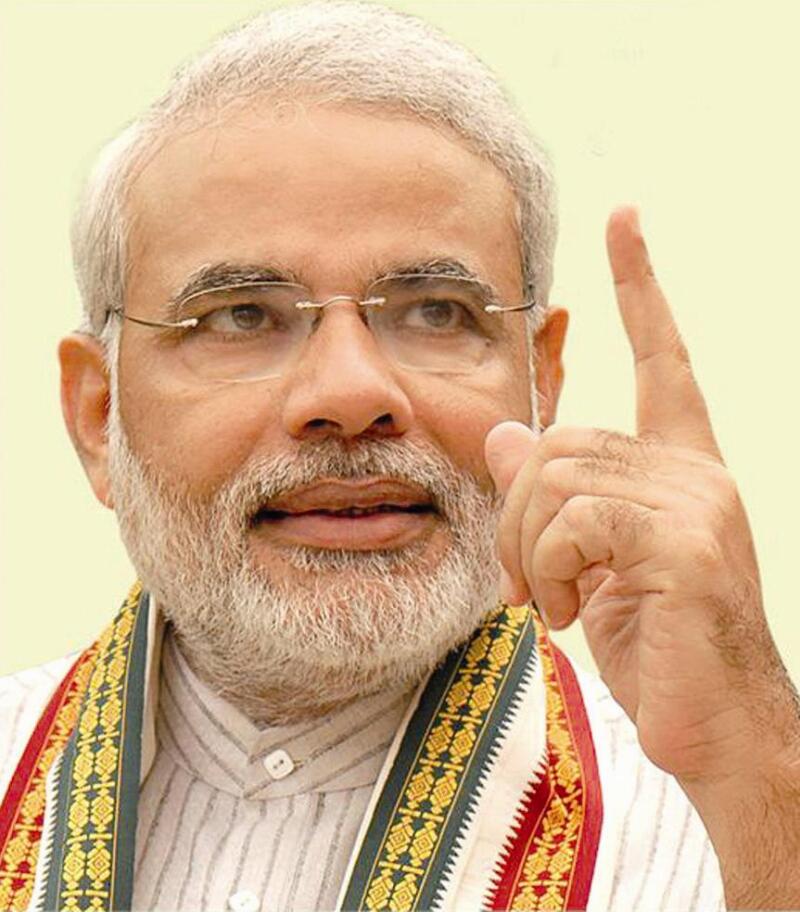

The success of Modi (right) and the BJP is built on part his reputation for cutting red tape and fostering economic growth in the state of Gujarat, where he had been serving as chief minister. During his term, Gujarat saw double-digit annual growth that outpaced the rest of the country. In 2011, The Economist dubbed Gujarat “India’s Guangdong”, the southern Chinese province that serves as not only the country’s major manufacturing region, but also the home of IP-savvy companies such as Tencent, ZTE and Huawei.

Big plans

The BJP’s plans for strengthening India’s economy may be of interest to IP owners. In its election manifesto, the BJP lists several IP-related plans, such as nurturing universities that specialise in fields such as intellectual property. There is also a plan to create specialised IP courts, which seems to be increasingly popular among countries looking to modernise their IP systems. The BJP also promises to “establish an Intellectual Property Rights Regime which maximizes the incentive for generation and protection of intellectual property for all type of inventors”, and, perhaps with a dash of bravado, hints at a plan to “embark on the path of IPRsand Patents in a big way”.

The manifesto also speaks of an ambitious plan to increase judicial efficiency that touches on a number of goals that if reached should benefit IP owners. Some highlighted tasks include filling judicial vacancies and addressing case backlogs, and a plan to double the number of lower level courts and judges. There are also plans to dedicate funds to modernise and increase the use of IT in the courts, create specialised fast-track commercial courts and devise a national litigation strategy to reduce pendency times.

Issue spotting

The promises of politicians often outstrip the realities of the final results, but at the very least, Modi and the BJP are aware of some of the issues facing businesses when using the judicial system. Some of the plans, such as those looking to modernise the courts and the creation of more electronic resources for lawyers, sound similar to the improvements that the India trade mark office has implemented. Similarly, the plans to reduce pendency through increasing manpower, including the very ambitious goal to double the number of lower court judges, echo the challenges faced by both the trade marks and patents registrars. Even if the improvements in manpower and modernisation fall a bit short of the stated targets, they may still yield very real improvements.

Mending fences

Another issue for India is its increasingly cantankerous relationship with the US over IP policy. Though multinationals are increasingly vocal in its criticism of India’s patentability standards and its granting of a compulsory licence for Bayer’s Nexavar, the US did not downgrade India in this year’s Section 301 Report. In fact, in early May, Commerce Secretary Rajeev Kher said that India will continue talks with the US on this issue after the election. Kher is expected to stay on despite the change of government and should offer some continuity in the discussions, though it is unclear if the BJP will ultimately take a much different tack from the previous government’s.

What do you think? Will the new government bring about big changes to India’s IP policies?