A&E’s reality show, Duck Dynasty, illustrates the principle that the true source of success often can be camouflaged. While the affable, bearded stars (right) clown around on screen, they are, in fact, well-educated, humble men of faith and family. Although Duck Dynasty depicts the comedic antics of Phil, Willie and Jase Robertson at the Duck Commander office, the real reality is that the Robertsons built a multi-million dollar empire by developing a unique product, capitalising on its novelty, and engaging in a systematic and well-conceived business strategy. It started with, of all things, a patent.

In the 1970s, the family’s patriarch, Phil Robertson, decided to forego his teaching career to pursue his passions of fishing and hunting in northeast Louisiana. To make ends meet, he planned to sell a duck call that he had invented. As with many entrepreneurs, however, he was faced with the daunting challenge of infiltrating an already-saturated market. Duck calls had been around for over a century, and competitors posed a roadblock.

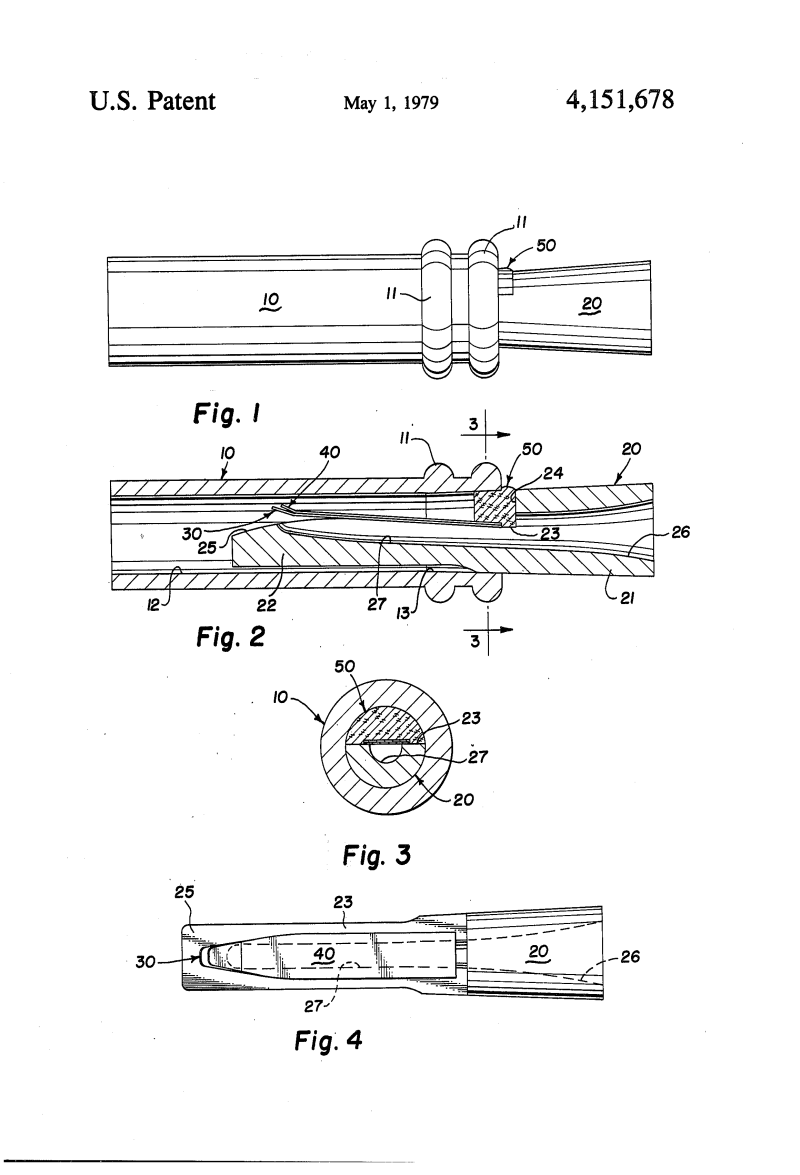

To distinguish his product, Robertson sought patent protection. In 1977, he filed an application for a utility patent, entitled Duck Caller. Robertson’s application detailed the structure of the apparatus, explaining that his invention had a specific advantage over prior duck calls because it could “simulate, nearly perfectly, the call of the mallard hen”. Two years later, the USPTO issued US patent number 4,151,678 (left). To be fair, Robertson’s patents did not instantaneously bestow success upon him. Rather, Robertson and his family engaged in a diligent and dogged marketing campaign (with a little luck and/or divine intervention). But the patent helped.

Robertson’s patent offered several business advantages.

First, Robertson’s patent gave him a marketing edge. As he sold duck calls out of the back of his truck, or lobbied Wal-Mart for shelf space, customers didn’t have to rely on his word. He could point to a certificate issued by the US government legitimising his innovative product. He could tout the distinction between his duck call and any competitive devices by explaining that the USPTO had concluded that his duck call was novel and useful.

Second, it permitted him the right to exclude others from his market. No one in the duck hunting industry could make a duck call that embodied the structure of his innovative product. If anyone copied his product, he could enforce his patents against them in court.

Third, if competitors had patents, he could employ his patents as a negotiating tool to gain access to their segment of the market, or overcome barriers to entry.

Fourth, his patent was an asset. If he desired to liquidate the value of his company, he could always license or sell his patents.

As Duck Commander infiltrated the market and its product line grew, Robertson continued to expand his intellectual property portfolio. He obtained US patents numbers 5,230,649 (“Duck call apparatus”) and 6,863,187 (“Gun support apparatus”). Interestingly, however, Robertson elected not to pay the maintenance fees on these patents, and allowed them to expire in 2001 and 2008 respectively. Thus, by 2001, all of Duck Commander’s patents on duck calls had expired. Duck Commander was exposed to the crosshairs of competition.

Perhaps as a result of this exposure, the duck call market became increasingly crowded and competitive. Amazon.com now lists almost 50 brands of duck calls, and over 500 product offerings, many of which appear to employ the structure previously patented by Robertson. Primos, for example, appears to rank as one of Duck Commander’s most intense competitors, offering over 100 animal calls. Moreover, Primos’s website boasts a large patent portfolio, which the “company’s patent attorneys, all committed bow-hunters, protect aggressively”.

Coincidentally, about 80% of Primos’s patents have issued since Robertson’s duck call patents expired in 2001. And true to the statements on its webpage, Primos has aggressively enforced its patents in federal courts. In 2004, Primos prevailed in a three-week patent infringement trial against Hunter’s Specialties, receiving more than $3 million in total damages (affirmed by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in 2006). Accordingly, Primos appears to be moving in on Duck Commander’s patent territory, and as a result, continues to gain market share.

To combat Primos’s gains in the market, it appears that Duck Commander is reinvigorating its patent position. Its recent product offerings highlight its innovative triple-reed duck calls, for which patents are now pending. As a result, there appears to be a patent shoot-out brewing in the duck ponds. Perhaps A&E’s next reality programme will involve a Battle of the Duck Call Superstars. Stay tuned!

The authors are partners in the Washington, D.C. office of Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner and can be reached at scott.popma@finnegan.com and oshaughm@finnegan.com.