The lawsuit, Already v Nike, may force brand owners to think twice about suing for trade mark infringement. If Already prevails, trade mark owners will no longer be able to automatically end litigation they have started by signing a covenant promising not to sue their competitors.

By signing the covenant, the brand owner aims to strip the district court of jurisdiction over the infringer’s declaratory judgment claim or counterclaim for cancellation of the mark. The same strategy is also frequently used in patent lawsuits.

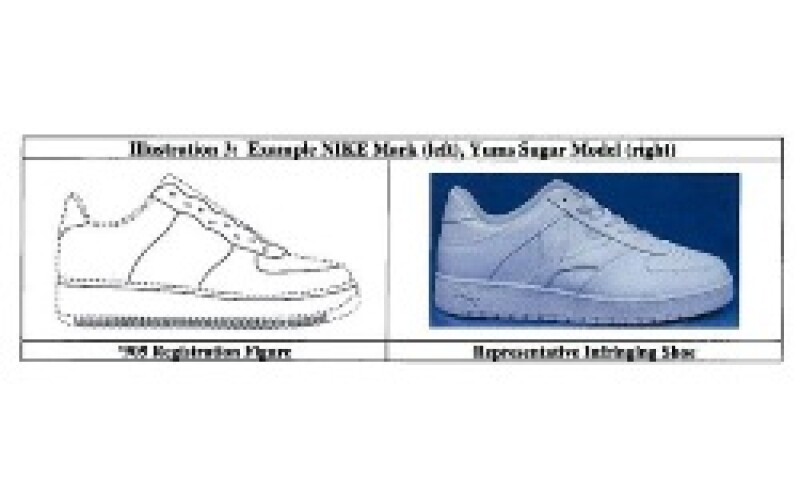

The dispute began in 2009 when Nike sued, claiming Already’s "Sugar" and "Soulja Boy" shoes (pictured) violated Nike’s trade mark covering design features of its “Air Force 1”, a low-cut sneaker. After Already countersued to invalidate the trade mark, Nike abandoned its claim and offered a covenant promising not to sue Already for copying the design.

Nike’s lawyer Thomas Goldstein, of Goldstein & Russell, told the US Supreme Court on Wednesday that the covenant negates the dispute. But James Dabney, representing Already, claimed his client still has a legitimate interest in getting the trade mark cancelled, since the covenant only covers current or previous designs or obvious spin-offs, not new designs.

Dabney, of Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson, argued that as a sports shoe manufacturer, Already is likely to produce a new shoe which falls outside the terms of the covenant in the future. Having already been sued by Nike, he said his client is more likely than other companies to be sued in future, and that the risk of litigation had deterred investors. Already is on Nike’s internal top 10 list of infringers.

Some justices seemed to regard this argument as speculative.

“To say you are in the business of producing new footwear, at least to me, suggests nothing, because the question is what the footwear looks like, not that you're producing new footwear,” said Justice Stephen Breyer.

Peter Brody, an IP partner of Ropes & Gray who has been following the case, said the case hinges on whether Already has a legitimate legal dispute with Nike as opposed to an academic disagreement.

“You get the sense as you read into the case that Already’s lawyer was stressing that Nike is trying to have it both ways and manipulating the system a little bit,” he said.

“On the other hand, there’s this pesky legal requirement that the case must be a live, pressing argument.”

He said Already has other options for pursuing cancellation, such as through the PTO’s appeal process, but acknowledged “a common perception among trade mark challengers that the PTO is friendlier towards trade mark owners than the courts”.

Katherine Basile, chair of the trade mark practice group at Novak Druce + Quigg, said a litigant’s advantage of being able to withdraw from a case is not exclusive to trade mark disputes.

She said if Nike had agreed not to sue Already over any future shoe, this could have put the brand at risk of appearing to have abandoned the mark.

“The courts have actually said that if you don’t enforce your trade mark rights you can lose them.”