One-minute read |

Counterfeiting can have a serious impact on businesses, consumers and governments. Therefore a strong anti-counterfeiting programme should be an integral part of a company’s operations. It is impossible to fully measure the impact of deterring counterfeiting, but companies can develop a scorecard on which the effectiveness of an anti-counterfeiting programme can be assessed. Steps can be taken to compile data on enforcement and, in due course, you may also want to evaluate consumer attitudes. With good planning, these metrics can be made integral to the anti-counterfeiting programme. |

Counterfeiting is widespread, and the negative impact of counterfeiting is felt in many ways. Consumers who unknowingly purchase counterfeit goods may form negative views of a company's product. Some counterfeit products may injure or even kill consumers. Over time, the perception of a product or a brand may be undermined by the misperceptions formed from lesser-quality counterfeit goods. The competition created by counterfeit goods may have an impact on the price of genuine goods, and the availability of counterfeit goods will divert consumers. This will have an impact on revenue and, in many instances, the counterfeit market will represent lost opportunities for a company.

What is more, a brand owner risks the threat of litigation. Litigation has been brought against brand owners seeking to hold them liable for damages caused by counterfeits. While the product liability theory advanced may turn the law on its head, a brand owner is more susceptible to claims if it fails to take appropriate action against counterfeiters.

At least one law professor has argued for civil remedies against manufacturers of genuine products that have been counterfeited. In an article in 8 Currents: International Trade Law Journal 43, Professor Arthur Best charged that, similar to states' requirements that all products be sold in reasonably safe condition, "[a] product marketed without reasonable anticounterfeiting measures could be characterized as defective in the sense that its labeling fails to reduce risks associated with the product". He claimed that, if it is foreseeable that a consumer will be injured as a consequence of his or her confusion between the authentic product and the counterfeit, "then basic principles of products liability law require that the defendant reduce the risk of that injurious confusion if there are practical ways to do so".

The United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida disagreed. In Schoenbaum v Procter & Gamble C. (in which the author was co-counsel for the defence), the plaintiffs charged that the manufacturer of legitimate products should be liable for any harm caused by counterfeit hair care products. The plaintiffs alleged that the manufacturer knew of counterfeit products that could have caused harm to purchasers and that the manufacturer knowingly defrauded consumers by actively promoting authentic products without warning purchasers of the potential harm of buying counterfeits.

The court rejected the claim, the judge stating from the bench: "I don't think since the beginning of the common law has there been a duty for someone to give notice to others that somebody is robbing from them."

Counterfeiting also takes its toll on the public. Counterfeiting has been associated with terrorists, organized crime, child labor, and big lost revenues for governments and businesses.

A strong anti-counterfeiting programme should be an integral part of a company's operations. In implementing such a programme, management should consider the nature of the products that may be counterfeited, and the production and distribution chain, to target counterfeiters as effectively as possible. While the full impact of deterring counterfeiting may be difficult to measure, it is possible to develop a scorecard of the conditions prior to the implementation of an anti-counterfeiting programme. The steps taken, and subsequent market conditions, will lead to an assessment of the impact of such a programme.

The challenge of measuring the impact of counterfeiting

The full impact of counterfeiting eludes quantification. Measuring the full effects of an anti-counterfeiting campaign would need to take into account direct and indirect factors, including revenue, pricing (of both the genuine and counterfeit goods), production capacity, consumer satisfaction, product and brand image and lost opportunities. This would also need to account for constantly changing markets and economic conditions. The benefits of precise quantification could readily be exceeded by the time and cost involved.

As a simple example, some consumers will knowingly purchase a counterfeit product and will regard the price as a good deal. Had the counterfeit not been available, a number of these consumers would not have purchased the genuine product at its market value. Eliminating the availability of the counterfeit product may not have a direct impact on revenues from such consumers, but the absence of the counterfeit product can have a direct effect on pricing, as well as on product and brand reputation. It is similarly difficult to measure the full impact of an anti-counterfeiting campaign. For example, a successful anti-counterfeiting campaign may not only eliminate the known counterfeiters, but also deter the entry of additional counterfeiters.

In addition, the impact of counterfeiting, and the benefits of an anti-counterfeiting campaign, are difficult to isolate. Again, as examples, suppression of counterfeiting may enable a company to sustain its pricing structure, but other variables, such as the presence of legitimate competitors or even general economic conditions, will also be factors in pricing decisions. A successful anti-counterfeiting campaign may drive up the costs, and thus the price charged by the counterfeit industry, or it may drive out all but those counterfeiters who offer the lowest quality product at the lowest price. The avoidance of damage from counterfeiting to a company's brand and reputation, which may be among its greatest assets, may also be the hardest measure to take.

Ways to measure an anti-counterfeiting programme

A company committed to brand integrity will want to protect its consumers, its brand value and otherwise minimise the damage that may be done by counterfeiters. Management will also want to take some measure of the effectiveness of its anti-counterfeiting programme.

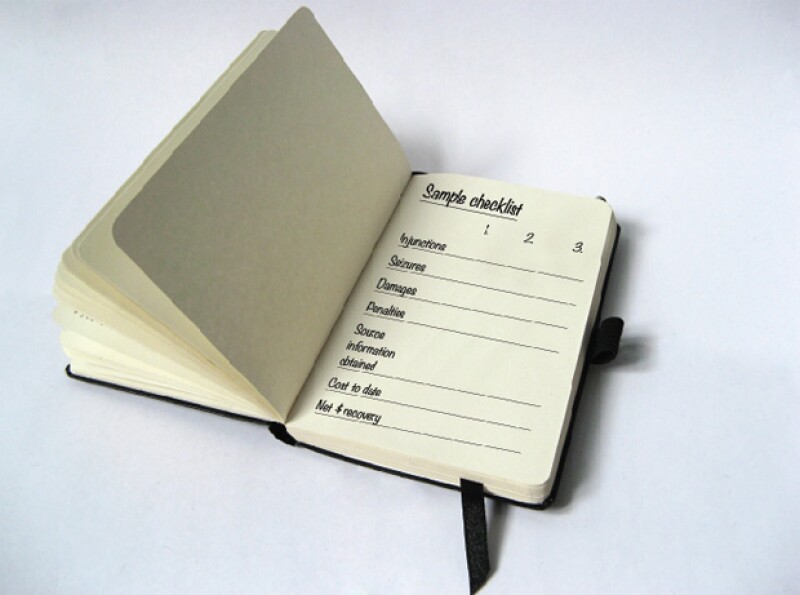

A data scorecard

A determination of what to measure will depend on the type of action that is taken. For example, an anti-counterfeiting programme may seek to stop the production of counterfeit goods at the plant, or the distribution of counterfeit goods at a port of entry or key distribution point. In such instances, the number of seized goods can be quantified. Additionally, an extrapolation may be made of the threat of further activities by the specific counterfeiting activities that were stopped by these efforts.

Measurements can also be taken from an anti-counterfeiting programme in local market areas. As an example, the following steps can be taken, from which specific data can be obtained:

Step 1: In an identified geographic market or markets, or identified sales channel, undercover investigators are engaged to shop for a product. This should yield information concerning the identity or number of counterfeit sellers, percent of counterfeit goods, and the price of the counterfeit goods in the identified market.

Step 2: A coordinated anti-counterfeiting enforcement programme is undertaken. This may take the form of civil litigation for injunctive relief and money damages. It may also include assisting in the development of criminal and administrative enforcement actions and resultant penalties. It may result in seizures of counterfeit goods. Through both civil and criminal litigation, source information may be obtained that will enable further enforcement activities.

Step 3: At a reasonable time after enforcement actions are underway, undercover investigators are engaged again to shop for the product. This should yield information about changes in the identity or number of counterfeit sellers, percent of counterfeit goods, and the price of the counterfeit goods.

If desired, a comparative assessment may also be made of the quality of the counterfeit goods surveyed in steps 1 and 3, in particular as that may relate to price.

Finally, the cost of the anti-counterfeiting programme can be included in the measurement.

Each of the factors can be put on a template, quantified and tracked. Examples of model templates can be seen on the previous page.

This model can be adapted for other forms of anti-counterfeiting programmes. For example, an anti-counterfeiting programme may be targeted at online sales. Online analysts or other investigators may monitor the internet, and the instances of online counterfeit product and the number of take-downs may be included in the template. Similarly, the template may be adapted to reflect whether the counterfeit activity that is uncovered takes the form of store sales or street sales. A variable may also be included for the enforcement timeline.

Measuring consumer attitude

An anti-counterfeiting programme may also include educating consumers as to the dangers of supporting the counterfeit marketplace and the benefits of purchasing genuine products. Also, as previously discussed, counterfeiting can have an impact on the reputation of a product, brand and business. Surveys of consumer attitudes in conjunction with either an educational campaign or an anti-counterfeiting programme may provide an additional means for measuring the effectiveness of such efforts.

However, before measuring consumer attitude, you should identify and understand corporate interests. To begin, you should consider whether the quantity or quality of anti-counterfeiting actions is significant. In industries where there are life-threatening counterfeits such as pharmaceuticals or aircraft parts, the measure of success may be different compared to luxury goods.

For example, in the pharmaceutical industry, a big success may be when investigative efforts identify and stop a breach of the legitimate supply regardless of the length of time and cost involved. Any number of successful investigations, civil judgments and criminal restitution may be less important than stopping the breach and entry of counterfeits into the legitimate supply chain.

In contrast, luxury goods companies may choose to measure success by the number of successful investigations, the quantity of civil seizures and criminal referrals, the number of counterfeits seized, and the size of judgments awarded.

A targeted approach to identify and stop key counterfeiting activities may be a measure of success for some companies or industries and not for others. And creative solutions such as court decisions holding landlords liable for counterfeiting activities on their premises may be significant for some companies but not others.

An additional consideration when measuring the success of an anti-counterfeiting programme revolves around publicity. Some companies abhor press reports about counterfeits; others crave and solicit them. Once you determine a corporation's view on such publicity, you can evaluate publicity gained or avoided as part of the overall success of a programme.

Finally, as mentioned above, the cost of an anti-counterfeiting programme may be part of a corporation's scorecard in assessing its success. Programmes may be designed in a way that makes them cost-neutral or even a profit centre for a company. Your cost expectations and goals are, of course, an element in measuring success.

Build metrics into the programme

An effective anti-counterfeiting programme starts with an understanding of the product, its place in the market, and the points of vulnerability to counterfeiting. It will play a vital role in safeguarding brand integrity. While the full impact of counterfeiting, and the concomitant benefit of a strong anti-counterfeiting programme, may not be fully measurable, it remains helpful for management to have some measure of the impact of these efforts. With a few steps, these metrics can be built into the design of the anti-counterfeiting programme.

|

Mark Mutterperl |

© 2012 Mark Mutterperl. The author is a partner in the New York office of Fulbright & Jaworski

On managingip.com |

Nissan’s lessons from the Middle East, June 2012 Should I set up a counterfeiting hotline?, July 2011 How to curb counterfeiting competitively, July 2010 Your guide to effective enforcement, June 2010 |