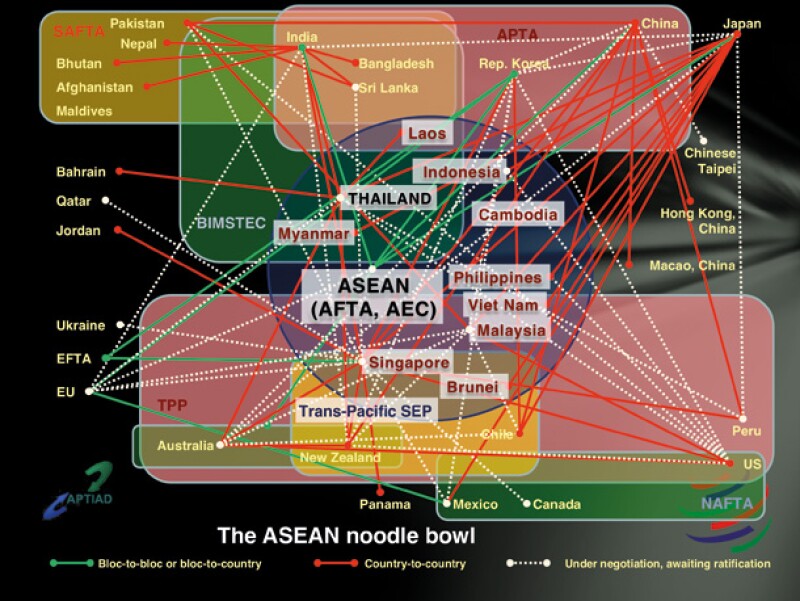

Is multilateralism dead? In the area of IP, it seems that way. There are some exceptions, of course: a niche WIPO-brokered treaty here, a clarification of the health implications of the TRIPs Agreement there – but there seems little reason for IP negotiators to stick around in Geneva. It's a trend that goes far beyond IP. In the years following the heady days of globalisation in the 1990s, there has been little agreement at international level on issues ranging from trade and the environment to taxation and military intervention. Many developing countries and NGOs argued that TRIPs, agreed in 1994, was stacked in favour of rich countries and declined to offer more concessions on IP protection. With CEOs and business organisations lining up to push for higher standards of IP protection, developed country governments adopted a new approach: if they couldn't get agreement among the WTO's 150-plus members, they would do deals with willing trading partners. The past 15 years have seen a rapid proliferation of bilateral and regional deals: the WTO says that there are now 379 in force. But what does it mean for IP?

Contents |

| Why IP owners should worry about bilateral treaties Behind the scenes at the Trans-Pacific Partnership |

Ratcheting up

Unlike multilateral deals to harmonise trade rules, free trade agreements allow two or more countries to grant each other preferential treatment not on offer to third parties. They can agree to lower tariffs on goods, for example, or to remove non-tariff barriers to trade. That's not the case with IP, however, because the TRIPs Agreement is based on the most-favoured nation (MFN) principle, which provides that countries can only agree to higher standards of IP protection on a bilateral basis if they extend that level of protection to all members of the WTO. Each new IP-related obligation in a free trade deal effectively ratchets up IP norms internationally.

Are FTAs good for IP owners?

IP owners – especially those in multinational companies – have plenty of reasons to like FTAs. Because TRIPs acts as a baseline of IP standards, FTA negotiations put IP owners in a no-lose position: they can only raise levels of IP protection. In practice that means longer copyright terms and a more patent-friendly legal environment (see TRIPs-plus box for more examples). The TRIPs Agreement's MFN clause means that higher standards agreed bilaterally become the new international norm – both legally and culturally.

The importance of normalising more stringent IP protection is illustrated by a letter written by BusinessEurope to the European Commission in May outlining its preferred outcome for the TTIP talks. "The agreement should strengthen the multilateral trading system by developing rules and standards in key areas (such as IPR, export restrictions, investment, and trade facilitation) that could be adopted beyond the transatlantic market," said the lobby group, adding: "The agreement should also address issues which go beyond the WTO's TRIPs obligations, in order to be a front-runner and a precedent for future multilateral rules."

FTAs also often introduce new dispute resolution mechanisms, bypassing the WTO's own procedures for resolving alleged violations of TRIPs. Although critics of TRIPs have traditionally claimed the deal was designed to benefit advanced economies, a number of IP wrangles brought before the dispute settlement body have been resolved in favour of developing countries. It's not surprising, then, that some IP owners would welcome a different venue for thrashing out disagreements, such as panels for hearing IP disputes provided for by FTAs. This is aligned to a trend towards rolling up investor protection provisions (once contained in stand-alone bilateral investment treaties, known as BITs) into free trade deals. Increasingly investors themselves – rather than the governments that are parties to the FTA – are able to seek redress for alleged breaches of their rights using investor-state arbitration. If the arbitrators are willing to treat IP rights as an "investment", then these souped-up FTAs offer IP owners a powerful tool to protect their rights. Such arbitrations may, however, lack the kinds of procedural safeguards such as transparency that are found at the multilateral level. "The WTO has rules of the game that are more clear and transparent," says Hafiz Aziz ur Rehman of Médecins Sans Frontières' Access Campaign. "We are concerned about investor-state arbitration. It's not just theoretical, as cases such as the claim being brought by Eli Lilly against Canada show. Canada might have the resources to defend itself – but how would a less-developed country respond?"

Another area where FTAs are changing the way that governments and IP owners can seek redress in IP trade rows relates to non-violation disputes. The WTO allows governments to complain to its dispute settlement body where they can show that the actions of another member state have deprived them of an expected benefit – even if they cannot show that the member has broken one of its WTO commitments. These so-called non-violation disputes proved particularly controversial in the area of IP, however, and there has been a moratorium on their use for TRIPs disputes since 1995.

A growing number of free trade deals, however, include non-violation provisions for IP. Although largely untested, they open up the possibility that one party could try to overturn tobacco plain packaging rules, for example, or price caps on patented drugs.

FTAs also offer IP owners the advantage of speed. While it took negotiators more than 15 years to conclude the treaty to protect audiovisual performances, and debates over a GI registry are in their second decade, bilateral negotiators can seal a deal in a matter of months.

Says Antony Taubman, head of the IP division at the WTO: "Sometimes trade agreements in particular sectors, such as wine, have included schedules of GIs. At the WTO, debates and negotiations on GIs are moving into their 14th year, with no outcome so far; this situation contrasts with bilateral deals when negotiators directly agree that certain GIs will be protected. The deals are done. It's an effective approach to negotiations in its way, as it settles the question directly, but we need to reflect more on the implications of this negotiating model for the fully international system."

That misfit between FTAs and the multilateral process is an important drawback of FTAs. Ask any IP association or trade negotiator and they will tell you that the multilateral process – where it's achievable – is best. After all, everyone wants to be seen as an inclusive, team player. Their responses might be rather disingenuous, given the benefits of FTAs to IP owners, but there are clear upsides to the multilateral process. First, it achieves a greater degree of harmonisation. FTAs are often criticised for leading to a patchwork of IP provisions, but Taubman says it's more accurate to describe the process as "layering", given that the language used in IP chapters rarely matches directly. "The IP provisions in FTAs are inspired by the same interests but often take a different form, which makes it very hard to extrapolate any emerging trends for the international law of IP in general," he says. This layering phenomenon can be particularly difficult for the officials back home who have to turn promises made in FTAs into domestic legislation without the kind of support offered by the WTO to help countries implement their TRIPs obligations.

"FTAs are not substitutes for national laws," says Taubman. "Any national IP law will be more detailed and complicated and have more individual features than any FTA. The impact of an FTA depends on how its provisions are interpreted and implemented. There are examples of countries agreeing to have higher standards of data exclusivity when they have no process for regulatory approval in the first place. The central challenge posed by this trend is not for IP owners directly, but for legal draftspeople trying to turn these agreements into national law and to ensure reasonable interoperability in practice, while safeguarding vital national policy interests."

But layering does have drawbacks for IP owners. The practical difficulties countries experience when they implement FTAs create the kind of uncertainty that businesses always dread. Then there are problems created by the deal-by-deal negotiating process. While this often allows richer countries to demand higher standards of IP protection from their trading partners, it also gives opponents the time to mobilise against provisions they dislike. That has certainly happened with the EU-India FTA. The EU is believed to have demanded India introduce data exclusivity rules but, following concerted opposition from activists and NGOs such as Médecins Sans Frontières, EU negotiators have now promised not to require India to agree to anything that would require changes to its IP laws. Talks have now stalled and few, including one of the EU's IP negotiators Anders Jessen, expect any progress soon. "It's true that the timeline for negotiations keeps on being stretched out and that's never good news. That said, the leads have not given up but it is getting more challenging," he says.

Backlash

The mothballing of the EU-India talks is part of a wider backlash against bilateral and regional deals, a trend that peaked with the sinking of the controversial anti-counterfeiting deal ACTA. Officials are keen to distinguish the IP-focused deal from wider-ranging free trade agreements and claim that its narrow scope contributed to its demise. That is because most trade deals are backed by a powerful alliance of domestic stakeholders – from agribusinesses to car makers – who work to convince politicians of the agreement's advantages. ACTA benefited a limited group of IP owners in the creative industries who were unable to counter co-ordinated and focused opponents.

ACTA offers plenty of lessons for IP negotiators who want to conclude more deals with willing trade parties. Jessen says that the Commission has taken them on board in its approach to the TTIP talks. "When you have two major trading parties each with its own template for negotiations, then if you try to draft language to cover both of the templates then you end up with language that is unclear," he says. "With ACTA, we drafted for EU law, but it also covered US law. We had endless discussions about the aims and went round in circles. So we need to avoid such broad drafting."

The EU trade negotiator adds that a deal may be easier to achieve if it steers clear of the enforcement of IP rights online and copyright. "Both issues are substantively controversial, and they are areas where opponents have been particularly effective at mobilising opposition."

Transparency concerns

Allegations of secrecy in the negotiating process also helped ensure ACTA's demise. Civil society groups angered by their inability to access draft texts allied with MEPs in the European Parliament cross that their role was simply to rubber stamp a done deal. Although Jessen denies that NGOs were shut out of the process while IP owners were favoured ("we get complaints from industry, too," he says), it is clear that countries negotiating new trade deals are making an effort to be seen to be more transparent. It's a tricky balancing act.

"There is always a tension about the ideal level of transparency," says Jessen. "We can't always force other parties to accept our levels of transparency. Sometimes we have been criticised but not all documents are ours to give. People won't negotiate if you won't respect their level of transparency and confidentiality."

Peter Bradwell, policy director of the Open Rights Group, which opposed ACTA, says that he has already seen a shift in the way that the UK government is dealing with stakeholders. Although UK negotiators are not at the TTIP table, officials from the country's IP Office and business ministry have been feeding the views of stakeholders to the European Commission. "The IPO has tried to be fair, to hold roundtables and to make people available for conversations," he says. For Bradwell, the key lesson of ACTA was to make the deal process itself more open. "It was very far removed from a democratic process. It was hard to find out who was in the negotiating room and who we had to talk to. It took a lot of resources." He urges the officials behind TTIP to spend more time on outreach and engagement earlier in the process. "Once negotiations start, it is hard to be too transparent. But there needs to be more open dialogue."

ACTA also gave IP owners a lesson in advocacy. Their business-as-usual approach to influencing negotiators through briefing papers and closed-door meetings looked clunky and proved inadequate up against nimble, social media-savvy opponents. Jessen says that stakeholders need to be more vocal if they want to be effective, and to remember that the European Parliament endorses trade deals. Ilias Konteas of BusinessEurope says his organisation plans to launch an IP advocacy and education project next year. "We are all aware of the post-ACTA environment," he says. "Although there were a lot of inaccuracies in the debate and things were spun in different ways, what is done is done. We want TTIP to be concluded and that means open constructive dialogue with all stakeholders – even those who are critical of the inclusion of an IP chapter."

EFPIA, which represents Europe's originator pharmaceutical companies, says it is also doing more work to defend its position and justify its FTA requests. The group has been running debates in the European Parliament about access to medicines, says Brendan Barnes, chair of its IP committee. "We invite our critics," he says. "We make a point of having a balanced platform."

Trade deals on the table |

||

There are dozens of trade talks taking place around the world at any one time. Here are two of the most important. Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)The first round of TTIP talks was held in Washington DC in July, where the parties met 350 stakeholders. A second round begins in October in Brussels. The European Commission has promised that ACTA provisions on IP rights enforcement in the digital environment and criminal sanctions will not be part of the TTIP negotiations. Geographical indications are likely to be one of the most controversial aspects of the IP chapter. Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)TTP is being negotiated by the US, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Peru, Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Canada, Mexico and Japan. The 19th round of talks was due to be held in Brunei at the end of August. Negotiations on the IP chapter include data exclusivity, patent term extension, the patentability of second medical uses and trade mark registrability.

|

The future of FTAs

Although the two WIPO treaties negotiated in the past 15 months suggest some hope of an upsurge in IP activity at the multilateral level, in reality there is no appetite for a new round of IP law harmonisation. But while emerging economies are reshaping power relationships and challenging old north-south certainties, old divisions over IP remain: developed countries gain most from strong protection. As such, they will push for IP chapters in FTAs wherever they have the negotiating leverage to do so. That might mean extracting plenty of IP concessions from small or poor countries, but few (or none) from more powerful partners.

But the trend towards regional and bilateral deals (ACTA excepted) poses challenges. "What do they [FTAs] add up to?" asks the WTO's Taubman. "It is an issue that should engage everyone. What are the systemic implications? On ACTA, both sides [of the debate] said it was a stepping stone to multilateralism. Is that true? How so, and is it desirable?"

With the WTO effectively sidelined from deal making, one suggestion is that it provide a more formal platform for coordinating IP agreements so that parties to them have a better understanding of what they might be promising to do. At the moment, there is a legitimate question about whether countries are progressively rewriting international law without the checks and balances of the multilateral system: not just on compulsory licences, patent term extension, and data exclusivity, but also on registration of trade marks, copyright standards and copyright term. That might be good for IP owners in the short-term, but it may not provide the level of buy-in that successful norm-setting needs for the long term.