The arguments

Proposing the motion last night, AI writer Calum Chace and legal consultant and author of The Naked Lawyer Chrissie Lightfoot argued that the exponential growth in computing power make it inevitable that computers will be able to perform routine legal work more efficiently than humans. Indeed, Lightfoot gave examples of law firms that already use AI in bankruptcy and real estate work, and to draft contracts and wills.

Searching prior art, assessing inventive step and drafting a patent application will soon be within the capabilities of computers, they argued, as will the search and examination work done by IP offices.

Countering, UK IPO senior examiner Nigel Hanley and Mathys & Squire partner Ilya Kazi conceded that AI would play an increasing role in patent work, in particular in searches, but that a human element would still be necessary. “AI will help me but not replace me,” said Hanley.

Hanley and Kazi developed two broad arguments to oppose the motion. First, they emphasised the “subjective” element. As Hanley said: “Patents are not a yes-or-no question” and judging patentability requires judgment about the law, cases and language. For example, he said the phrase “a row of cells” in a patent application could have at least nine different meanings.

Moreover, said Kazi, AI would need to identify not just the patentable invention but also the clients’ particular needs: for example, an SME on a tight deadline might require a different service to a multinational with an unlimited budget. Only a (human) patent attorney can provide this.

Second, they raised the issue of “trust”, asking whether the public would be comfortable for a machine to grant a monopoly right without human supervision. It’s like driverless trains, said Hanley: even if the technology exists, people prefer the reassurance of seeing a human face at the controls.

This trust issue raised a further question about whether the law would be reformed within 25 years to allow non-human patent granting. As Kazi said: “Even for just one patent to be granted, the whole system needs to change.”

Embrace change

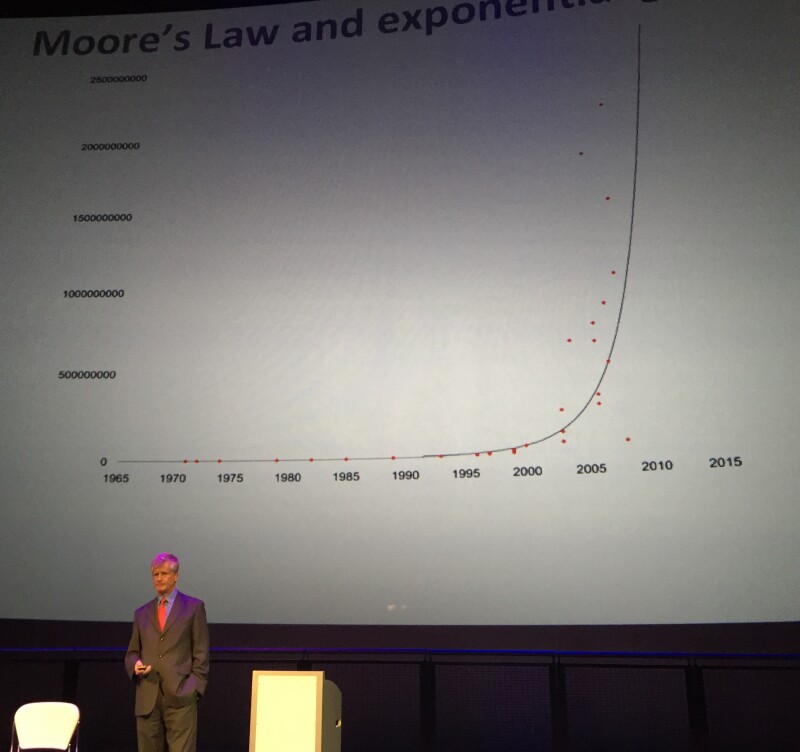

Last night’s debate followed a provocative discussion at the CIPA Congress last month led by writer John Straw. In a powerful talk, filled with fascinating examples, he explained how AI, 3D printing, robotics, virtual reality and the internet of things will “disrupt everything” and destroy many professional jobs once computing power overtakes brain power (which could be within 20 years). Just as the industrial revolution meant the decline of farm labourers, said Straw, the next generation could see computers replace teachers, engineers, doctors, lawyers and IP attorneys. (And, if it’s any consolation to readers, journalists and editors too.)

It sounds scary. But arguably those that embrace technological change will benefit, while those that resist it will fail. Lawyers who develop and use smart tools for case management, evidence selection and drafting will be able to save clients money while also spending their own time on more sophisticated, high-value work.

Reasons to be cheerful

The audience last night voted roughly 80-60 in favour of the motion “This House believes it is inevitable that, within 25 years, a patent will be filed and granted without human intervention”. (Unfortunately, there was no computer available to provide an accurate count.) I think those of us voting “Yes” were strongly persuaded by the optimism and enthusiasm of the advocates of AI, but many of us were also sceptical of some of the arguments against the motion.

Subjectivity may be part of the patent system, but wouldn’t efforts to reduce or even remove it be in the interests of most users? The promise of greater predictability and consistency would, I expect, be more important for many people.

Then there is the question of whether the law needs to change at an international level to allow a computer to grant a patent. This could indeed delay all-computer filing beyond the 25-year period envisaged in the motion. But many national patent laws and practices have adapted to cope with new developments, including e-filing, machine translation and online searching. There’s reason to think that, at least in some jurisdictions, more use of AI could be accepted easily enough. In fact, it would be a pity if broadly welcome technological improvements were held up by legal bickering and vested interests.

The majority support for the motion should make patent attorneys and paralegals sit up. But others working in the IP ecosystem should also take note. If we believe computerised patent granting will be with us in 25 years, how much sooner could we expect computerised granting of trade mark or design applications (for example)?