Those baying for reform often point to patent trolls creating a crisis in patent litigation that must be addressed. It is true that patent trolls have become an increasing issue in the past decade; it is also true that some are overstating the effect of patent trolls on litigation.

A new analysis from Lex Machina underlines this point. Following up on its Patent Litigation Year in Review report released in May – which revealed that the number of patent litigation cases was up 12.4% in 2013 – the legal analytics firm has delved deeper into its figures to work out what is driving them.

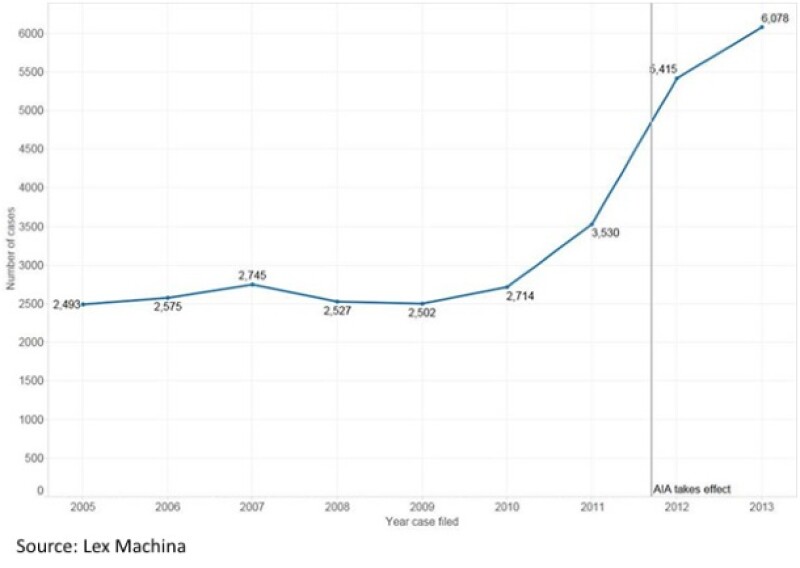

In a new blog post, Lex Machina noted that the number of new cases had indeed risen greatly in recent years – as can be seen in the chart below.

This kind of chart is often used by those arguing that trolls are causing patent litigation to boom. But much of the big jump that can be seen between 2010 and 2013 is not a result of trolls but rather (and perhaps ironically) by patent reform.

The America Invents Act, which became effective in 2011, changed the procedural rules regarding joinder. Whereas previously a plaintiff could sue multiple defendants in a single case, after September 2011 plaintiffs have had to bring a separate case against each defendant. It is this change that is responsible for much of the rise in patent cases since 2011, according to Lex Machina’s figures.

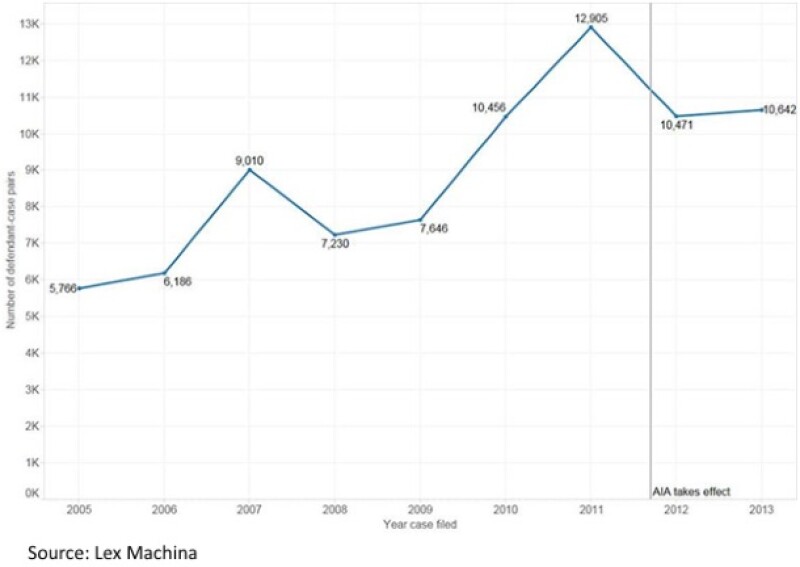

Analysing the figures by the number of defendants rather than simply the number of cases paints a starkly different picture. By this measure, there was a big increase in 2010 and 2011 but then a big fall in 2012 and only a 1.6% increase in case filings in 2013.

Lex Machina notes in is blog post: “Examining this same data (counting a case multiple times, once for each defendant) on a month-by-month basis shows that, in the peak year of 2011, most of the activity occurred in the month of the implementation of the AIA (September 2011). In contrast to the charts above simple counting cases that suggest litigation is on the rise, the recent years of 2012 and 2013 are relatively consistent with…the earlier years of 2010 and 2011 when counting cases by defendants to neutralize the effects of the AIA, with the exception of September 2011.”

(emphasis in original)

This finding is consistent with a report issued by the Government Accountability Office in August last year. That report found that from 2000 to 2010 the number of patent infringement lawsuits in the federal courts fluctuated slightly, and from 2010 to 2011 the number of such lawsuits increased by about a third. That report too identified the changes in the AIA as the biggest influence on this.

The GAO said non-practising entities (NPEs) brought about a fifth of all lawsuits. The office’s analysis also found that lawsuits involving software-related patents accounted for about 89% of the increase in defendants over this period.

None of this is to say that patent trolls are not engaging in egregious behaviour that needs to be addressed. Many are.

Lex Machina in its new analysis estimated the role of what it terms patent monetization entities by looking at cases where the plaintiff filed at least 10 cases a year counting by defendants compared with cases where the plaintiff filed fewer than 10 cases. It found that litigation by low-volume infrequent plaintiffs has remained “remarkably consistent” over the past nine years, with a 6% change from year to year. In contrast, those filing cases with more than 10 defendants has seen a rapid increase, increasing from 2,983 in 2005 to 7,828 in 2013 – peaking at 11,618 in 2011.

But it is worth noting that the GAO in its report did not advocate further legislation, instead pointing to the role USPTO could play in addressing the problem at source, by clamping down on overly broad patents that can be abused by trolls.

The GAO recommended: “The Secretary of Commerce should direct the Director of PTO to consider examining trends in patent infringement litigation, including the types of patents and issues in dispute, and to consider linking this information to internal data on patent examination to improve the quality of issued patents and the patent examination process.”

What is not acknowledged by some proponents of patent reform is that there have been many recent changes that are already affecting patent trolls. One is the PTAB trials established under the AIA that allow the validity of patents to be challenged. Another is the Supreme Court’s Octane decision in April that relaxed the rules for fee shifting, increasing the chance of patent trolls having to pay attorneys fees if bringing meritless lawsuits (this has already had an effect on patent trolls). Most recently came the long-awaited Alice v CLS decision from the Supreme Court , which some interpreted as bad news for trolls.

On the last point, Michael Gulliford, managing principal of patent management firm Soryn IP, recently noted in an article for TechCrunch: “What is clear, however, is that the weapon of many non-practicing entities (more commonly known as ‘patent trolls’) – the business-method software patent – is likely dead. Why? Because these patents generally relate to the use of known computer methods to implement known ways of doing business – the hallmark of invalidity under the Supreme Court’s new decision.”

With so many moving parts, it may be wise for lawmakers to see how they play out for a while before looking to overhaul the whole thing again.

In the meantime, slimmed down reform targeting demand letter abuse is being touted in Congress. When lawmakers talk about patent trolls, they almost all give the example of a coffee shop owner being told that she is infringing a patent by using wifi in its shop. This type of narrower legislation would go some way to clamping down on this nefarious behaviour.

But supporters of broad reform are opposed to this legislation. The CCIA, for example, says it is “worse than no legislation” and that tools to level the litigation field are also needed.

The opposition to slimmed down legislation is likely driven by the concern that it would replace the chance of broader reform further down the road. But with hopes of comprehensive reform dead for now, and unclear but positive effects from developments elsewhere, maybe they should take what they can get.